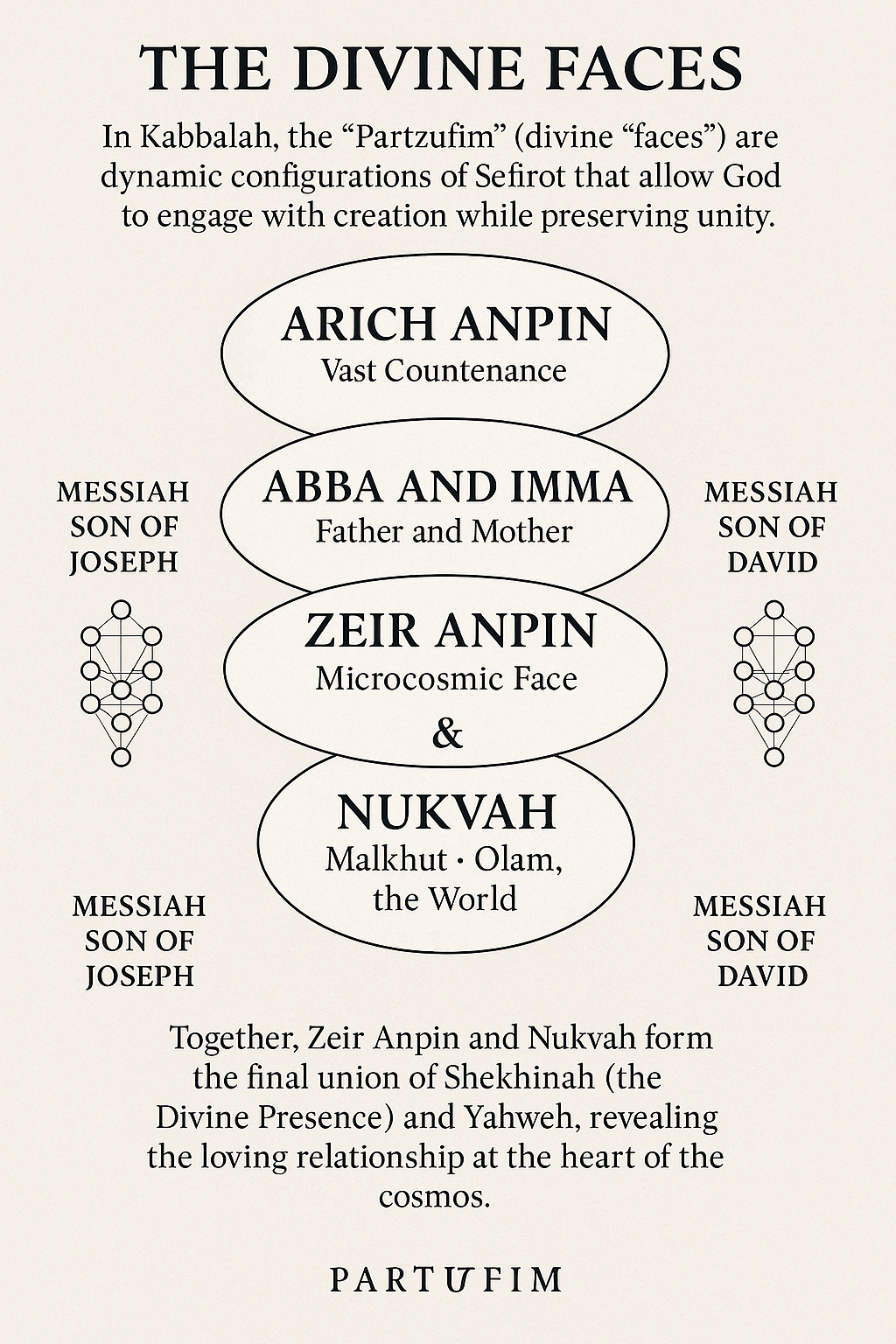

The concept of Partzufim (singular: Partzuf) represents one of the most profound developments in the mystical understanding of God. While the earlier system of Kabbalah, particularly in the Zohar, described the Sefirot as individual attributes or emanations of the Divine, the system of Partzufim takes this a step further: it shows how these attributes can be rearranged and integrated into whole “faces” or configurations of divine consciousness. These are not literal faces, but archetypal personae through which Ein Sof (the Infinite) expresses itself in relational form. They allow the Infinite to interact with the finite world in structured, meaningful ways, facilitating a dynamic and living interface between God and creation.

There are five primary Partzufim that emerge from the original ten Sefirot: Arikh Anpin (the Long Face), Abba (Father), Imma (Mother), Zeir Anpin (the Short or Small Face), and Nukva (the Female or Shekhinah). Each Partzuf corresponds to a set of Sefirot acting in unison, not as isolated forces but as an integrated spiritual organism. This reconfiguration makes it possible to understand how different aspects of divine interaction—mercy, judgment, wisdom, presence—function in harmony, each in their appointed time and place.

Arikh Anpin represents the supernal will of God, the first stirring of desire within Ein Sof to create. It is rooted in Keter, the highest of the Sefirot, and is associated with infinite compassion, long-suffering, and non-reactivity. Arikh Anpin is the divine patience that sustains creation even when it falters. It is not active in the sense of intervention but passive and overarching, like a cosmic background of mercy.

Abba and Imma, corresponding to Chokhmah and Binah respectively, represent the intellectual or conceptual powers of God. Abba is divine wisdom, the flash of insight that sees the whole at once, while Imma is understanding, the slow, methodical nurturing of ideas into form. Their union is necessary for any new reality to be conceived. Abba and Imma are sometimes seen as the “parents” of Zeir Anpin, just as thought precedes emotion and structure follows inspiration.

Zeir Anpin is the most complex and relatable of the Partzufim. It corresponds to the emotional Sefirot from Chesed through Yesod. Zeir Anpin is the aspect of God that governs time, emotion, relationship, and response. It is also the configuration most closely related to the Messiah—the Son. In the divine drama, Zeir Anpin is the divine persona that walks among creation, feeling, acting, and mediating between the higher world and the lower.

Opposite Zeir Anpin is Nukva, the feminine presence of God, also known as the Shekhinah. Composed primarily of the Sefirah Malkhut, Nukva is the vessel that receives the light of Zeir Anpin and transmits it to the world. In this capacity, she represents the immanent presence of God—the Divine as it is experienced in the world of action, suffering, exile, and return. She is also the archetypal Bride, the one who longs to reunite with her Husband (Zeir Anpin or ultimately Ein Sof), and in this process mirrors the human soul’s own yearning for the Divine.

The necessity of Partzufim arises from the need to bridge the infinite with the finite. If the Sefirot were left as abstract forces, they would remain inaccessible to the human mind and heart. By embodying them in archetypal configurations, the Partzufim allow humans to meditate on, relate to, and ultimately unite with the Divine. They make the transcendent knowable without diminishing its mystery. They are how God communicates with His creation—through faces, through forms, through relational archetypes.

In messianic terms, Yahweh—the Father—corresponds to Arikh Anpin and Abba, the source of will and wisdom. His incarnation into the world can be seen as a descent into the configuration of Zeir Anpin, the Son, who acts in the world, expresses divine emotion, and serves as a channel for redemption. The Shekhinah, or Nukva, is both the world and the Bride—she receives, reflects, and ultimately reunites with the divine source. Their union restores the world and brings about the ultimate Tikkun, or rectification.

Each Partzuf is composed of all ten Sefirot within its structure but arranged in a manner that reflects its unique function. For example, Zeir Anpin has a Keter, Chokhmah, and Binah of its own, even though it begins at Chesed. This recursive structure reflects the fractal nature of divine reality in Kabbalah—every part contains the whole. The Partzufim interact with one another through spiritual dynamics known as zivugim (unions), hashpaot (influences), and tikkunim (repairs). These interactions drive the flow of divine light through the cosmos and determine the spiritual conditions of each generation.

Ultimately, Partzufim represent the mystery of how God, who is absolutely One, can appear as many without losing unity. They are the “faces” through which the One becomes known, loved, and served. Through them, the Infinite becomes intimate. They are the divine theater in which the drama of existence unfolds, and the sacred masks God wears to step into the world He created.

Throughout biblical history, different Partzufim become predominant based on the spiritual state and mission of each generation. During the time of Abraham, the Partzuf of Abba (Divine Father) is especially active, manifesting as divine wisdom guiding Abraham’s journey into the unknown and establishing the covenant of faith. In the days of Moses, Imma (Divine Mother) becomes dominant—her Binah guides the formation of Israel’s law and national identity. At Sinai, the divine speech flows from the womb of understanding into structured revelation.

Zeir Anpin becomes the primary interface in the wilderness and the early monarchy. As the small face—emotional, kingly, relational—it reflects God’s guidance through the ups and downs of Israel’s spiritual maturity. Its union with Nukva (the Shekhinah) is essential for maintaining divine presence within the camp, the Temple, and the heart of communal worship.

During the exile, the presence of the Shekhinah is described as going into exile with Israel. In this era, Nukva takes on the suffering of the world, reflecting the collective pain of disconnection. The repair (tikkun) of Nukva becomes the goal of prayer and mitzvot, raising sparks to restore her stature and prepare for union with Zeir Anpin once again.

In the person of Yeshua (Jesus), Kabbalistic thinkers see a manifestation of the Messiah ben Yosef, associated with Zeir Anpin—embodying the small face of God in humility and sacrifice. His mission is one of preparing the bride (Nukva), undergoing suffering, and rectifying the lower worlds. His crucifixion is seen as a profound zivug—a moment of mystical union and elevation through pain.

At the end of days, it is said that Arich Anpin—the macrocosmic face of the Father—will become fully revealed. This corresponds to Messiah ben David, whom some associate with Yahweh Himself, descending to dwell among His creation as the unifying Partzuf that harmonizes all others. He completes the tikkunim of Zeir Anpin and Nukva, revealing the full light of Keter and uniting all worlds.

Other biblical moments can also be interpreted through this lens. The building of the Tabernacle corresponds to a temporary alignment of all Partzufim, with Chokhmah and Binah (Abba and Imma) providing the design, Zeir Anpin channeling the divine energy, and Nukva—the actual structure—receiving and manifesting the indwelling Presence. The destruction of the Temple represents a severing of this alignment, a cosmic exile.

The patriarchs and matriarchs are embodiments of specific Partzufic traits. Abraham reflects Chesed (within Zeir Anpin), Isaac Gevurah, Jacob Tiferet. Sarah channels Binah, Rebecca Chesed, Leah and Rachel aspects of Malkhut. David is a vessel of Malkhut being elevated toward union, and Solomon’s Temple represents a momentary marriage of all divine aspects.

Every generation of Israel, every prophet, and every historical moment can thus be seen as a movement within the theater of divine Partzufim—some drawing down light, others repairing rupture, all moving toward the final unification of the Infinite and the finite in one eternal embrace.